RansomGuard : an anti-ransomware filter driver

Intro

Ransomware is one of the simplest, yet significant threats facing organizations today. Unsuprisingly, the rise and continuing development of ransomware led to a plentitude of research aimed at detecting and preventing it. AV vendors, independent security reseachers and academies all proposing various solutions to mitigate the threat. In this blogpost we introduce RansomGuard, a filesystem minifilter driver designed to stop ransomware from encrypting files through the use of the filter manager. We also discuss the concepts and ideas that led to the design of RansomGuard, and the challenges we encountered in its implementation. RansomGuard’s source can be found here

Overview

- Introduction & the motivation behind the framework

- working with and managing contexts

Tracking & Evaluating file handles

- Truncated files

- Cleanup vs Close

- FatCheckIsOperationLegal

- Filters walkthrough

- RansomGuard against WannaCry

- Memory mapped files usage by Ransomwares

- Synchronous flush

- Asynchronous mapped page writer write

- Building asynchronous context

- Filtering Paging I/O

- “Blocking” a mapped page writer write

- RansomGuard against Maze

- How NTFS & FAT handle file deletions

- Racing deletes

- Extending the driver

- RansomGuard against yet another ransomware variation

The filter manager

The filter manager (FltMgr.sys) is a system-supplied kernel-mode driver that implements and exposes functionality commonly required in file system filter drivers. It provides a level of abstraction allowing driver developers to invest more time into writing the actual logic of the filter rather than writing a body of “boiler plate” code. Speaking of boiler plate code , writing a legacy file-system filter driver that does nothing can take up to nearly 6,000 lines of code. The filter manager essentially serves as a comprehensive “framework” for writing file system filter drivers. The framework provides the one legacy file system filter driver necessary in the system (fltmgr.sys), and as I/O requests arrive at the filter manager legacy filter device object, it invokes the registered minifilters using a call out model. After each minifilter processes the request, the filter manager then calls through to the next device object in the device stack, if any. Putting it simply, we can use the filter manager to register callbacks to be invoked pre and post a file-system operation as if our driver was part of the file-system device stack. In case you are not familiar with the filter manager API I suggest to review the related docs before proceeding with the article, mainly FLT_REGISTRATION. It’s important to note that easy to write does not mean easy to design, which remains a fairly complex task with minifilters, of course - depending on the minifilter’s task in hand. Nevertheless it makes it possible to go from design to a working filter in weeks rather than months, which is great.

Minifilter contexts

A context is a structure defined by a minifilter driver that can be associated with an object. The filter manager provides support for minifilter drivers to associate contexts with objects and preserve state across I/O operations.

Contexts are extremley useful, and can be attached to the following objects :

- Files

- Instances

- Streams

- Stream Handles (File Objects…)

- Transactions

- Volumes

Depending on the file system there are certian limitations for attaching contexts, e.g The NTFS and FAT file systems do not support file, stream, or file object contexts on paging files, in the pre-create or post-close path, or for IRP_MJ_NETWORK_QUERY_OPEN operations. A minifilter can call FltSupports*Contexts to check if a context type is supported for the given operation.

Context managment

Context management is probably one of the most frustrating parts of maintaining a minifilter, your unload hangs? it’s often down to incorrect context managment. This is one (of many) reasons to why you should always enable driver verifier.

The filter manager uses reference counting to manage the lifetime of a minifilter context, whenever a context is successfully created, it’s initialized with a reference count of one. Whenever a context is referenced, for example by a successful context set or get call, the filter manager increments the reference count of the context by one. When a context is no longer needed, it’s reference count must be decremented. A positive reference count means that the context is usable, when the reference count becomes zero, the context is unusable, and the filter manager eventually frees it. Lastly, note the filter manager is the one responsible for derefencing the Set* reference, it does that in the following conditions:

- The attached to system structure is about to go away. For example, when the file system calls

FsRtlTeardownPerStreamContextsas part of tearing down the FCB, the Filter Manager will detach any attached stream contexts and dereference them. - The filter instance associated with the context is being detached. Again taking the stream context example, during instance teardown after the InstanceTeardown callbacks have been made the filter manager will detach any stream contexts associated with this instance from their associated

ADVANCED_FCB_HEADERand dereference them.

Context registration

A minifilter passes the following structure to FltRegisterFilter to register context types

typedef struct _FLT_CONTEXT_REGISTRATION {

FLT_CONTEXT_TYPE ContextType;

FLT_CONTEXT_REGISTRATION_FLAGS Flags;

PFLT_CONTEXT_CLEANUP_CALLBACK ContextCleanupCallback;

SIZE_T Size;

ULONG PoolTag;

PFLT_CONTEXT_ALLOCATE_CALLBACK ContextAllocateCallback;

PFLT_CONTEXT_FREE_CALLBACK ContextFreeCallback;

PVOID Reserved1;

} FLT_CONTEXT_REGISTRATION, *PFLT_CONTEXT_REGISTRATION;

The ContextCleanupCallback is called right before the context goes away , useful for releasing internal context resources

Detecting encryption

To detect encryption of data we are going to leverage Shannon Entropy. We will assume the entire file is going to be encrypted, whilst partial encryption is mentioned towards the end of the article. Two datapoints are needed - one that represents the initial state of the file and another that represents the modified state of the file. We will use the follwing measurement, which was based on statistical tests performed against a large set of files of different types. It takes into account the initial entropy of the file, limiting false positives that may arise due to high entropy file types. (e.g. archives).

// statistical logic to determine encryption

bool evaluate::IsEncrypted(double InitialEntropy, double FinalEntropy)

{

if (InitialEntropy == INVALID_ENTROPY || FinalEntropy == INVALID_ENTROPY || InitialEntropy <= 0)

return false;

double EntropyDiff = FinalEntropy - InitialEntropy;

// the lower the initial entropy is the higher the required diff to be considered encrypted

double SuspiciousDIff = (MAX_ENTROPY - InitialEntropy) * 0.83;

if (FinalEntropy >= MIN_ENTROPY_THRESHOLD && (EntropyDiff >= SuspiciousDIff || (InitialEntropy < ENTROPY_ENCRYPTED && FinalEntropy >= ENTROPY_ENCRYPTED) ) )

return true;

return false;

}

0.83 was found to be the sweet spot value for the coefficient between detecting encrypted files and limiting false positives.

Ransomware variations

Let’s talk about ransomwares. When attempting to mitigate ransomware all variants of the encryption process must be considered, as it can happen very differently.

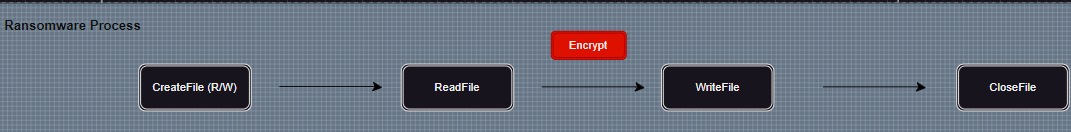

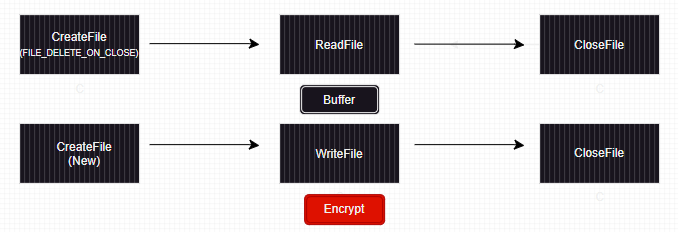

The most popular variation is where the files are opened in R/W, read and encrypted in place, closed and then (optionally) renamed.

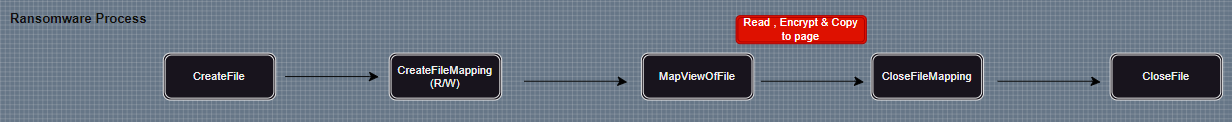

Another option is memory mapping the files, from a ransomware prespective not only that it’s faster, it is considered more evasive as the write is initiated asynchronously by the system process rather than by the ransomware process. (really anything asynchronous is harder to deal with from a defensive point of view). This trick alone was enough for Maze, LockFile and others to evade some well known security solutions.

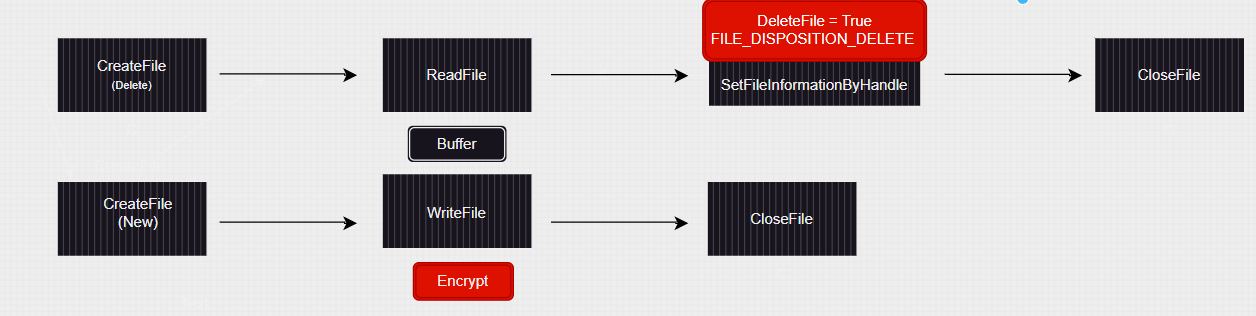

A third way could be creating a copy of the file with the new name, opened for W, the original file is read, its encrypted content is written inside and the original file is deleted. Whilst there are other possiblities which RansomGuard is not going to cover (check Wrapping Up for disclaimers), we are going to tackle those three variants as they are (by far) the most commonly seen in ransomwares in the wild. We will walkthrough RansomGuard’s design to deal with each variation seperatley, as each sequence of operations requires it’s own filtering logic and heuristics.

Tracking & Evaluating file handles

To start with, we will tackle the most obvious sequence seen in ransomwares

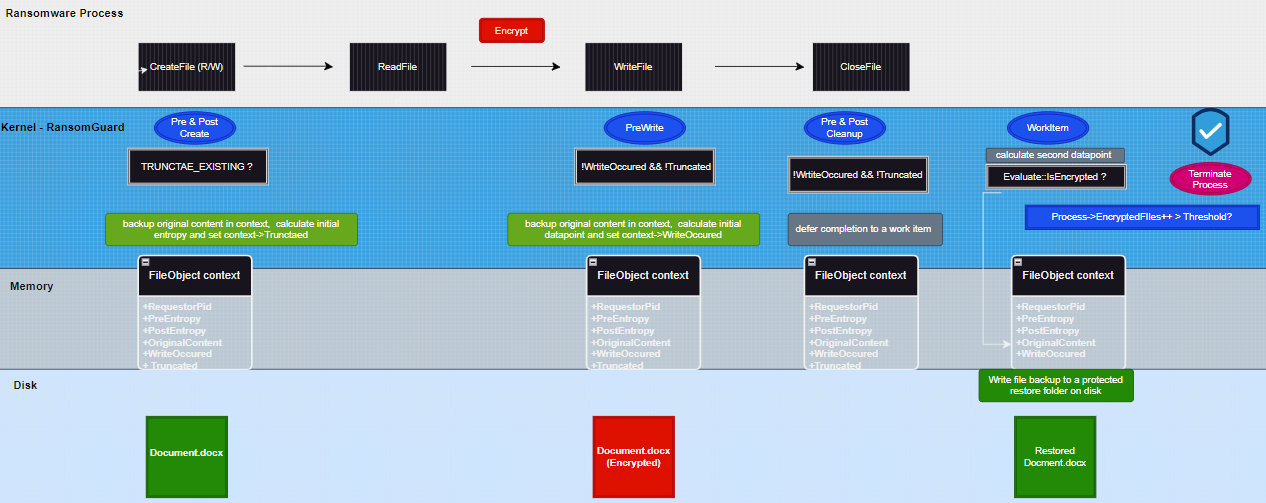

There are a couple of things to highlight:

- A file may be truncated when opened, consequently by the time our filter’s post create callback is invoked the initial state of the file is lost.

- A ransomware may initiate several writes using different byte offsets to modify different portions of the same file.

Considering #1, we will monitor file opens that may truncate the file, indicated by a CreateDisposition value of FILE_SUPERSEDE , FILE_OVERWRITE or FILE_OVERWRITE_IF. In such cases the initial state of the file is captured in pre create, otherwise it is captured when the first write occurs - in pre write.

Considering #2 , we have to distinguish between close and cleanup operations. IRP_MJ_CLEANUP is sent whenever the last user reference to the file is closed (e.g. the last handle is closed). In contrast IRP_MJ_CLOSE is sent whenever the last reference is released from the file object, representing the system state. Really what we want here is a datapoint when the file can no longer be modified using the same file object. Whenever I need a reminder of what’s allowed in post cleanup, I go to the FAT source code and look for the check it does. The following can be seen in the FatCheckIsOperationLegal :

//

// If the file object has already been cleaned up, and

//

// A) This request is a paging io read or write, or

// B) This request is a close operation, or

// C) This request is a set or query info call (for Lou)

// D) This is an MDL complete

//

// let it pass, otherwise return STATUS_FILE_CLOSED.

//

if ( FlagOn(FileObject->Flags, FO_CLEANUP_COMPLETE) ) {

PIO_STACK_LOCATION IrpSp = IoGetCurrentIrpStackLocation( Irp );

if ( (FlagOn(Irp->Flags, IRP_PAGING_IO)) ||

(IrpSp->MajorFunction == IRP_MJ_CLOSE ) ||

(IrpSp->MajorFunction == IRP_MJ_SET_INFORMATION) ||

(IrpSp->MajorFunction == IRP_MJ_QUERY_INFORMATION) ||

( ( (IrpSp->MajorFunction == IRP_MJ_READ) ||

(IrpSp->MajorFunction == IRP_MJ_WRITE) ) &&

FlagOn(IrpSp->MinorFunction, IRP_MN_COMPLETE) ) ) {

NOTHING;

} else {

FatRaiseStatus( IrpContext, STATUS_FILE_CLOSED );

}

}

Of course other file systems might allow other things, but FAT is always a good baseline. Clearly, a non paging write (ignore paging I/O, we will deal with that later) is not allowed, so it’s safe to assume the file will not be modified after the handle is closed by the user which makes post cleanup just about good enough to be used as our second datapoint. The following diagram summarizes RansomGuard’s design for evaluating operations across the same handle.

Next, let’s walkthrough each filter.

For the full implementation of the filters check out the filters.cpp source.

PreCreate

The PreCreate filter is responsible to filter out any uninteresting I/O requests. For now, we are only interested in file opens for R/W from UserMode. In addition, PreCreate serves as our only chance to capture the initial state of truncated files, if the file might get truncated, we read the file, calculate it’s entropy, backup it’s contents in memory and pass it all to PostCreate.

Lastly, we use this filter to enforce access restrictions :

- The restore directory should be accessible only from kernel mode.

- The user can connect to RansomGuard’s filter port and issue a control to copy the files to a user-accessible location.

- The user can connect to RansomGuard’s filter port and issue a control to copy the files to a user-accessible location.

- A process marked as malicious(ransomware) is blocked from any file-system access.

Let’s walkthrough the code , starting with the encforcment of file-system access restrictions :

// block any file-system access by malicious processes

ProcessesListMutex.Lock();

pProcess ProcessInfo = processes::GetProcessEntry(FltGetRequestorProcessId(Data));

if (ProcessInfo)

{

if (ProcessInfo->Malicious)

{

ProcessesListMutex.Unlock();

DbgPrint("[*] blocked malicious process from file-system access\n");

Data->IoStatus.Status = STATUS_ACCESS_DENIED;

Data->IoStatus.Information = 0;

return FLT_PREOP_COMPLETE;

}

}

ProcessesListMutex.Unlock();

// block any usermode access to the restore directory

FilterFileNameInformation FileNameInfo(Data);

if (!FileNameInfo.Get())

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

status = FileNameInfo.Parse();

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

if (restore::IsRestoreParentDir(FileNameInfo->ParentDir) && Data->RequestorMode == UserMode)

{

DbgPrint("[*] blocked usermode access to the restore directory\n");

Data->IoStatus.Status = STATUS_ACCESS_DENIED;

Data->IoStatus.Information = 0;

return FLT_PREOP_COMPLETE;

}

We are not interested in requests coming from the system or not for writing :

// Skip kernel mode or non write requests

const auto& params = Data->Iopb->Parameters.Create;

if (Data->RequestorMode == KernelMode

|| (params.SecurityContext->DesiredAccess & FILE_WRITE_DATA) == 0 )

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

Handling TRUNCATE_EXISTING opens :

// if file might get truncated , check if it exists and if so capture our initial datapoint here

if (CreateDisposition == FILE_OVERWRITE || CreateDisposition == FILE_OVERWRITE_IF || CreateDisposition == FILE_SUPERSEDE)

{

bool NotExists = utils::IsFileDeleted(FltObjects->Filter, FltObjects->Instance, &FileNameInfo->Name);

if (!NotExists)

{

CreateContx->Truncated = true;

CreateContx->PreEntropy = utils::CalculateFileEntropyByName(FltObjects->Filter, FltObjects->Instance, &FileNameInfo->Name, FLT_CREATE_CONTEXT, CreateContx);

if (CreateContx->PreEntropy == INVALID_ENTROPY)

{

FltFreePoolAlignedWithTag(FltObjects->Instance, CreateContx, TAG);

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

}

CreateContx->CalculatedEntropy = true;

}

}

A process notify routine managed linked list is used to track active processes in the system and maintain per-process state across different file objects and operations. Each process described by the following struct :

typedef struct _Process

{

ULONG Pid;

ULONG OriginalPid;

ULONG ParentPid;

PUNICODE_STRING ImagePath;

int FilesEncrypted;

LIST_ENTRY* Next;

bool Suspicious;

bool Malicious;

bool Terminated;

pSection SectionsOwned;

int SectionsCount;

Mutex SectionsListLock;

pDeletedFile DeletedFiles;

int DeletedFilesCount;

Mutex DeletedFilesLock;

} Process, * pProcess;

Since we use a statistical logic to identify encryption, a threshold number of encrypted files by a process must be met before we consider it as ransomware. The EncryptedFiles counter is used for that matter, and the rest of the structure will make sense later on in the blogpost.

PostCreate

post create , if the file is not new and the file system supports file object contexts for the given operation we initialize our context structure and attach it to the file object, the context is defined as below.

typedef struct _HandleContext

{

PFLT_FILTER Filter;

PFLT_INSTANCE Instance;

UNICODE_STRING FileName;

UNICODE_STRING FinalComponent;

ULONG RequestorPid;

bool WriteOccured;

bool Truncated;

double PreEntropy;

double PostEntropy;

PVOID OriginalContent;

ULONG InitialFileSize;

bool SavedContent;

}HandleContext, * pHandleContext;

Walking through the code , we start by checking for file object contexts support and filter out new files :

pCreateCompletionContext PreCreateInfo = (pCreateCompletionContext)CompletionContext;

if (Flags & FLTFL_POST_OPERATION_DRAINING || !FltSupportsStreamHandleContexts(FltObjects->FileObject) || Data->IoStatus.Information == FILE_CREATED)

{

if (PreCreateInfo->SavedContent)

ExFreePoolWithTag(PreCreateInfo->OriginalContent,TAG);

FltFreePoolAlignedWithTag(FltObjects->Instance, CompletionContext, TAG);

return FLT_POSTOP_FINISHED_PROCESSING;

}

Next we allocate, initialize and attach thecontext to the file object.

pHandleContext HandleContx = nullptr;

NTSTATUS status = FltAllocateContext(FltObjects->Filter, FLT_STREAMHANDLE_CONTEXT, sizeof(HandleContext), NonPagedPool, reinterpret_cast<PFLT_CONTEXT*>(&HandleContx));

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

{

if (PreCreateInfo->SavedContent)

ExFreePoolWithTag(PreCreateInfo->OriginalContent, TAG);

FltFreePoolAlignedWithTag(FltObjects->Instance, CompletionContext, TAG);

return FLT_POSTOP_FINISHED_PROCESSING;

}

...

// initialization of context stripped for readabilty , check out filters.cpp for the initialization code.

...

status = FltSetStreamHandleContext(FltObjects->Instance, FltObjects->FileObject, FLT_SET_CONTEXT_KEEP_IF_EXISTS, reinterpret_cast<PFLT_CONTEXT>(HandleContx), nullptr);

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

{

FltReleaseContext(HandleContx);

return FLT_POSTOP_FINISHED_PROCESSING;

}

FltReleaseContext(HandleContx);

return FLT_POSTOP_FINISHED_PROCESSING;

}

PreWrite

If the file object is monitored (has a context attached to it), and if it’s the first write using the file object and the file was not truncated during create, we will capture the initial state of the file.

// filtering logic for all types of I/O other than paging I/O

pHandleContext HandleContx = nullptr;

status = FltGetStreamHandleContext(FltObjects->Instance, FltObjects->FileObject, reinterpret_cast<PFLT_CONTEXT*>(&HandleContx));

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

AutoContext AutoHandleContx(HandleContx);

// we already have a datapoint

if (HandleContx->WriteOccured || HandleContx->Truncated)

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

HandleContx->WriteOccured = true;

HandleContx->PreEntropy = utils::CalculateFileEntropy(FltObjects->Instance, FltObjects->FileObject, HandleContx, true);

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

Within the utils::CalculateFileEntropy utility, the original content of the file is backed up in the context.

Entropy = utils::CalculateEntropy(DiskContent, FileInfo.EndOfFile.QuadPart);

if (InitialEntropy && Context)

{

Context->OriginalContent = DiskContent;

Context->InitialFileSize = FileInfo.EndOfFile.QuadPart;

Context->SavedContent = true;

}

PreCleanup

Again , we simply check here if the file is monitored and whether the file has been modified. If not there’s no need to evaluate the context.

pHandleContext HandleContx = nullptr;

NTSTATUS status = FltGetStreamHandleContext(FltObjects->Instance, FltObjects->FileObject, reinterpret_cast<PFLT_CONTEXT*>(&HandleContx));

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

// no write occured , no need to evaluate

if (!HandleContx->WriteOccured && !HandleContx->Truncated)

{

FltReleaseContext(HandleContx);

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

}

// pass handle context pointer to post cleanup

*CompletionContext = HandleContx;

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_WITH_CALLBACK;

PostCleanup

At this point the file cannot be modified using the same file object , due to IRQL restrictions capturing the second datapoint must be deferred to a worker thread, this is done by returning FLT_POSTOP_MORE_PROCESSING_REQUIRED.

pHandleContext HandleContx = (pHandleContext)CompletionContext;

if (!HandleContx)

return FLT_POSTOP_FINISHED_PROCESSING;

if (Flags & FLTFL_POST_OPERATION_DRAINING)

{

// release get reference from pre close

FltReleaseContext(HandleContx);

return FLT_POSTOP_FINISHED_PROCESSING;

}

// continue completion processing asynchronously at passive level

PFLT_DEFERRED_IO_WORKITEM EvalWorkItem = FltAllocateDeferredIoWorkItem();

if (!EvalWorkItem)

{

FltReleaseContext(HandleContx);

return FLT_POSTOP_FINISHED_PROCESSING;

}

NTSTATUS status = FltQueueDeferredIoWorkItem(EvalWorkItem, Data, evaluate::EvaluateHandle, DelayedWorkQueue, reinterpret_cast<PVOID>(HandleContx));

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

{

FltFreeDeferredIoWorkItem(EvalWorkItem);

FltReleaseContext(HandleContx);

return FLT_POSTOP_FINISHED_PROCESSING;

}

return FLT_POSTOP_MORE_PROCESSING_REQUIRED;

The evaluate::EvaluateHandle work item

VOID evaluate::EvaluateHandle(PFLT_DEFERRED_IO_WORKITEM FltWorkItem, PFLT_CALLBACK_DATA Data, PVOID Context)

{

pHandleContext HandleContx = (pHandleContext)Context;

ULONG FileSize = 0;

HandleContx->PostEntropy = utils::CalculateFileEntropyByName(HandleContx->Filter, HandleContx->Instance, &HandleContx->FileName, FLT_NO_CONTEXT, nullptr);

if (evaluate::IsEncrypted(HandleContx->PreEntropy, HandleContx->PostEntropy))

{

if (HandleContx->OriginalContent && HandleContx->InitialFileSize > 0)

{

if (NT_SUCCESS(restore::BackupFile(&HandleContx->FinalComponent, HandleContx->OriginalContent, HandleContx->InitialFileSize)))

DbgPrint("[*] backed up %wZ\n", HandleContx->FileName);

}

processes::UpdateEncryptedFiles(HandleContx->RequestorPid);

}

FltReleaseContext(HandleContx);

FltFreeDeferredIoWorkItem(FltWorkItem);

FltCompletePendedPostOperation(Data);

}

Where the processes::UpdateEncryptedFiles function is responsible to increase the process’s EncryptedFiles counter and kill it if the threshold is met.

RansomGuard against WannaCry

Knowing WannaCry follows the CreateFile -> ReadFile -> WriteFile -> CloseFile sequence, we tested what we have so far against it :

- 10 files encrypted , 10 of which RansomGuard restored !

- successfully killed WannaCry

- Debug output :

00000296 167.18316650 [FltMgr] Mini-filter verification enabled for "RansomGuard" filter.

00000297 167.19189453 [*] RansomGuard protection is active!

00000391 217.50335693 [*] Encryption Detected

00000392 230.13081360 [*] backed up \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\9781118127698.jpg

00000393 230.14079285 [*] files encrypted by \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\WannaCry.exe -> 1

00000411 236.85186768 [*] Encryption Detected

00000412 236.95446777 [*] backed up \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\IMG-20170621-WA0005.jpg

00000413 236.96711731 [*] files encrypted by \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\WannaCry.exe -> 2

00000421 238.28771973 [*] Encryption Detected

00000422 238.31800842 [*] backed up \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\IMG-20170623-WA0009.jpg

00000423 238.32882690 [*] files encrypted by \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\WannaCry.exe -> 3

00000424 239.00428772 [*] [\Device\HarddiskVolume3\Windows\Prefetch\CMD.EXE-6D6290C5.pf] pre write 7643 post close 7640 diff -3

00000427 239.56579590 [*] [\Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\IMG_20170704_104906.jpg] pre write 7971 post close 8000 diff 29

00000428 239.58071899 [*] Encryption Detected

00000429 239.69236755 [*] backed up \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\IMG_20170704_104906.jpg

00000430 239.70263672 [*] files encrypted by \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\WannaCry.exe -> 4

00000439 241.63113403 [*] Encryption Detected

00000440 241.70027161 [*] backed up \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\IMG_20180228_170753.jpg

00000441 241.71061707 [*] files encrypted by \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\WannaCry.exe -> 5

00000444 243.08477783 [*] [\Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\IMG-20141130-WA0000.jpg] pre write 7971 post close 7999 diff 29

00000445 243.09956360 [*] Encryption Detected

00000446 243.24313354 [*] backed up \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\IMG-20141130-WA0000.jpg

00000447 243.25639343 [*] files encrypted by \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\WannaCry.exe -> 6

00000461 248.49011230 [*] Encryption Detected

00000462 248.49717712 [*] backed up \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\IMG_20190620_082327.jpg

00000463 248.50477600 [*] files encrypted by \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\WannaCry.exe -> 7

00000465 248.52275085 [*] Encryption Detected

00000466 248.52947998 [*] backed up \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\LICENSE.txt

00000467 248.53729248 [*] files encrypted by \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\WannaCry.exe -> 8

00000468 248.55439758 [*] backed up \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\Screenshot_20230308-232838_Gallery.jpg

00000469 248.56340027 [*] files encrypted by \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\WannaCry.exe -> 9

00000473 249.27931213 [*] Encryption Detected

00000474 249.43690491 [*] backed up \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\Screenshot_20230325-185808_Chrome.jpg

00000475 249.44566345 [*] files encrypted by \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\WannaCry.exe -> 10

00000476 249.45210266 [*] killed ransomware process!

Filtering Memory Mapped I/O

Usage of memory mapped files to perform the encryption has become more and more common around ransomware families over the years, which makes it harder for behavior based anti-ransomware solutions to keep track of what is going on due to the nature of memory mapped I/O.

A file mapping is essentially a section object , with CreateFileMapping being a wrapper around NtCreateSection.

To write to a mapped file , an application maps a view of the file to the process and operates on the pages backing the view directly, when modified the corresponding PTEs are marked dirty and when the virtual address range is flushed or unmapped the dirty PTE bit is “pushed out” to the PFN (i.e. the Modified bit gets set). Mofidied PFNs are written out back to storage asynchronously by one of the page writers, for file backed sections by the mapped page writer, and for pagefile backed sections by the modified page writer.

From the ransomware perspective this is great, the actual write to the file seems as if it was originated from the system process, it can even happen after the process is terminated, and since the ransomware process itself only interacts with memory rather than disk , it’s also much faster.

Our goal is to be able not only to detect those mapped page writer encryptions , but to pinpoint back at the malicious process behind them.

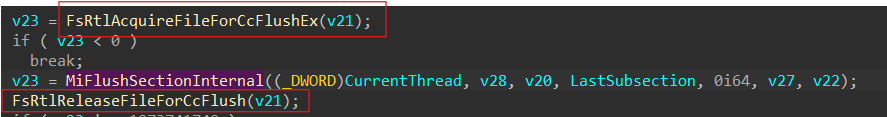

Synchronous flush

Whilst I personally haven’t seen such usage in ransomwares, an application can explictly call FlushViewOfFile to flush changes back to storage synchronously , in which case the nature of the paging write is different.

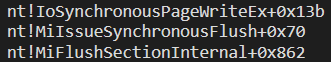

FlushViewOfFile maps to MmFlushVirtualMemory in ntos , which in turn calls MmFlushSectionInternal as shown below :

The call to MmFlushSectionInternal is followed by the following callstack :

Clerarly , MmFlushSectionInternal , where the actual write is initiated , is surrounded by two FsRtl callbacks :

FsRtlAcquireFileForCcFlushEx-IRP_MJ_ACQUIRE_FOR_CC_FLUSH(before the write)FsRtlReleaseFileForCcFlushEx-IRP_MJ_RELEASE_FOR_CC_FLUSH(after the write)

Most importantly, for a synchronous flush the write is initiated from the caller’s context , perhaps why it’s unlikely to see it used in a ransomware.

Asynchronous mapped page writer write

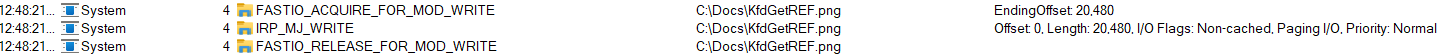

In contrast, for an asynchronous mapped page writer write two different FsRtl callbacks are invoked.

FsRtlAcquireFileForModWriteEx-IRP_MJ_ACQUIRE_FOR_MOD_WRITE(before the write)FsRtlReleaseFileForModWriteEx-IRP_MJ_RELEASE_FOR_MOD_WRITE(after the write)

This can be easily seen in MiMappedPageWriter -> MiGatherMappedPages which eventually calls IoAsynchrnousPageWrite or alternatively, in Procmon with advanced output enabled.

Note IRP_MJ_RELEASE_FOR_MOD_WRITE is typically invoked as part of a special kernel APC , and always runs at IRQL == APC_LEVEL.

Altough not used in RansomGuard, using the Acquire/Release callbacks as two datapoints to filter memory mapped I/O writes is a possability.

Building asynchronous context

To connect between a mapped page writer write and the process that memory mapped the file, we have to monitor the creation of section objects.

The heuristic idea is to assume any process that created a R/W section object for the file might be the one that modified the mapping and triggered the aysnchronous write, that means , whenever our minifilter sees a mapped page writer encryption , we will traverse each process and check if it ever created a R/W section for file in question , if so , it’s EncryptedFiles counter will be increased.

The odds for two different processes (one being a ransomware and the other being legitimiate) , to create R/W section objects for the same X number of files , and for those X number of files to also get encrypted are very slim to say the least , and so is the risk for false positives.

To track the creation of section objects we can filter IRP_MJ_ACQUIRE_FOR_SECTION_SYNCHRONIZATION, we are only interested in the creation of R/W section objects from UserMode :

if(Data->Iopb->Parameters.AcquireForSectionSynchronization.SyncType == SyncTypeCreateSection && Data->Iopb->Parameters.AcquireForSectionSynchronization.PageProtection == PAGE_READWRITE && Data->RequestorMode == UserMode)

If that’s the case:

- If not attached yet, a file context is allocated and attached to the file, initialized with the file name.

- the name of the file being mapped is added to a linked list (

SectionsOwned) of files mapped by the process (under the process entry structure).

// if a new r/w section was created

if (Data->Iopb->Parameters.AcquireForSectionSynchronization.SyncType == SyncTypeCreateSection && Data->Iopb->Parameters.AcquireForSectionSynchronization.PageProtection == PAGE_READWRITE && Data->RequestorMode == UserMode)

{

pFileContext FileContx = nullptr;

AutoContext Contx(nullptr);

// allocate a file context if it does not exist yet

NTSTATUS status = FltGetFileContext(FltObjects->Instance, FltObjects->FileObject, reinterpret_cast<PFLT_CONTEXT*>(&FileContx));

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

{

status = FltAllocateContext(FltObjects->Filter, FLT_FILE_CONTEXT, sizeof(FileContext), NonPagedPool, reinterpret_cast<PFLT_CONTEXT*>( &FileContx));

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

Contx.Set(FileContx);

FilterFileNameInformation FileNameInfo(Data);

if (!FileNameInfo.Get())

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

// init context

status = FileNameInfo.Parse();

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

FileContx->FileName.MaximumLength = FileNameInfo->Name.MaximumLength;

FileContx->FileName.Length = FileNameInfo->Name.Length;

if (FileNameInfo->Name.Length == 0 || !FileNameInfo->Name.Buffer)

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

FileContx->FileName.Buffer = (WCHAR*)ExAllocatePoolWithTag(NonPagedPool, FileNameInfo->Name.MaximumLength, TAG);

if (!FileContx->FileName.Buffer)

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

RtlCopyUnicodeString(&FileContx->FileName, &FileNameInfo->Name);

FileContx->FinalComponent.MaximumLength = FileNameInfo->FinalComponent.MaximumLength;

FileContx->FinalComponent.Length = FileNameInfo->FinalComponent.Length;

if (FileNameInfo->FinalComponent.Length == 0 || !FileNameInfo->FinalComponent.Buffer)

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

FileContx->FinalComponent.Buffer = (WCHAR*)ExAllocatePoolWithTag(NonPagedPool, FileNameInfo->FinalComponent.MaximumLength, TAG);

if (!FileContx->FinalComponent.Buffer)

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

RtlCopyUnicodeString(&FileContx->FinalComponent, &FileNameInfo->FinalComponent);

// attach context to file

status = FltSetFileContext(FltObjects->Instance, FltObjects->FileObject, FLT_SET_CONTEXT_KEEP_IF_EXISTS, FileContx, nullptr);

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

}

else

{

Contx.Set(FileContx);

}

DbgPrint("[*] R/W section is created for %wZ\n", FileContx->FinalComponent);

// add section entry in process structure

AutoLock<Mutex>process_list_lock(ProcessesListMutex);

pProcess ProcessEntry = processes::GetProcessEntry(FltGetRequestorProcessId(Data));

if (!ProcessEntry)

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

sections::AddSection(&FileContx->FileName, ProcessEntry);

}

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

Filtering paging I/O

Paging I/O is a term used to describe I/O initiated by either the Mm (memory manager) or Cc (cache manager). For paging reads, it means the page is being read via the demand paging mechanism, and rather than the virtual address of a buffer we are given an MDL that describes the newly allocated physical pages, the read is of course non cached as it must be satisifed from storage.

For paging writes, it means something within the Virtual Memory System (either Mm or Cc) is requesting that data within the given physical pages will be written back to storage by the file-system driver, much like with a paging read, to flush out dirty pages the O/S builds an MDL to describe the physical pages of the mapping and sends the non-cached, paging write.

We know memory mapped I/O, regardless if synchronous (explicit flush) or asynchronous (mapped / modified page writer or even a lazy writer write) comes in the form of noncached paging I/O. Up until now, such I/O has been indirectly filtered out as NTFS does not provide support for file object contexts in the paging I/O nor we allocated contexts for requests coming from the system. Since now we have to filter paging I/O coming from the system, we can add the following check before the file object context probe in our pre write filter.

// not interested in writes to the paging file

if (FsRtlIsPagingFile(FltObjects->FileObject))

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

// if noncached paging I/O and not to the pagefile

if (FlagOn(Data->Iopb->IrpFlags, IRP_NOCACHE) && FlagOn(Data->Iopb->IrpFlags, IRP_PAGING_IO))

Next, we are going to check if the file has a file context attached to it, as we are only interested in noncached paging writes to files that have been previously mapped by UM processes.

pFileContext FileContx;

// if there's a file context for the file

status = FltGetFileContext(FltObjects->Instance, FltObjects->FileObject, reinterpret_cast<PFLT_CONTEXT*>(&FileContx));

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

Since the mapped page writer flush precisly takes one write, we can reliably capture both of our datapoints at pre write. We have the state of the file before the write and we know what is going to be written. RansomGuard simulates the write in memory as demonstrated below:

auto& WriteParams = Data->Iopb->Parameters.Write;

if (WriteParams.Length == 0)

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

// retrive the data to be written

if (WriteParams.MdlAddress != nullptr)

{

DataToBeWritten = MmGetSystemAddressForMdlSafe(WriteParams.MdlAddress, NormalPagePriority | MdlMappingNoExecute);

if (!DataToBeWritten)

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

}

// no mdl was provided so use buffer

else

{

DataToBeWritten = WriteParams.WriteBuffer;

}

DataCopy = ExAllocatePoolWithTag(NonPagedPool, WriteParams.Length, TAG);

if (!DataCopy)

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

// read file from disk and make a copy of it

ULONG FileSize = utils::GetFileSize(FltObjects->Instance, FltObjects->FileObject);

if (FileSize == 0)

{

ExFreePoolWithTag(DataCopy, TAG);

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

}

PVOID DiskContent = utils::ReadFileFromDisk(FltObjects->Instance, FltObjects->FileObject);

if (!DiskContent)

{

ExFreePoolWithTag(DataCopy, TAG);

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

}

// make a copy of the buffer , must be done in try-except since there's a possibility it's a user buffer.

__try {

RtlCopyMemory(DataCopy,

DataToBeWritten,

WriteParams.Length);

}

__except (EXCEPTION_EXECUTE_HANDLER) {

ExFreePoolWithTag(DiskContent, TAG);

ExFreePoolWithTag(DataCopy, TAG);

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

}

// simulate a write in memory

SIZE_T SimulatedSize = (FileSize > WriteParams.ByteOffset.QuadPart + WriteParams.Length) ? FileSize : WriteParams.ByteOffset.QuadPart + WriteParams.Length;

PVOID SimulatedContent = ExAllocatePoolWithTag(NonPagedPool,SimulatedSize, TAG);

if (!SimulatedContent)

{

ExFreePoolWithTag(DiskContent,TAG);

ExFreePoolWithTag(DataCopy, TAG);

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

}

RtlCopyMemory(SimulatedContent, DiskContent, FileSize);

RtlCopyMemory((PVOID)((ULONG_PTR)SimulatedContent + WriteParams.ByteOffset.QuadPart), DataCopy, WriteParams.Length);

Now that we have two datapoints we can evaluate the contents in our buffers :

// evaluate buffers

PreEntropy = utils::CalculateEntropy(DiskContent, FileSize);

PostEntropy = utils::CalculateEntropy(SimulatedContent, FileSize);

double EntropyDiff = PostEntropy - PreEntropy;

DbgPrint("[*] [%wZ] pre paging write %d predicted paging write %d diff %d\n", FileContx->FileName, (int)ceil(PreEntropy * 1000), (int)ceil(PostEntropy * 1000), (int)ceil(EntropyDiff * 1000));

if (evaluate::IsEncrypted(PreEntropy, PostEntropy))

{

ULONG RequestorPid = FltGetRequestorProcessId(Data);

// synchronohs -> explicit flush

if (FlagOn(Data->Iopb->IrpFlags, IRP_SYNCHRONOUS_PAGING_IO) && RequestorPid != SYSTEM_PROCESS)

{

DbgPrint("[*] %wZ encrypted by %d\n", FileContx->FileName, RequestorPid);

processes::UpdateEncryptedFiles(RequestorPid);

}

// asynchronous -> mapped page writer write

else

{

DbgPrint("[*] %wZ encrypted by mapped page writer\n",FileContx->FileName);

processes::UpdateEncryptedFilesAsync(&FileContx->FileName);

}

if (NT_SUCCESS(restore::BackupFile(&FileContx->FileName, DiskContent, FileSize)))

DbgPrint("[*] backed up %wZ\n", FileContx->FinalComponent);

}

If the operation is synchronous, we are in the caller’s context and can evaluate normally. Otherwise, we call processes::UpdateEncryptedFilesAsync in which we increment the EncryptedFiles counter of any process that previously created a R/W section object for the encrypted file.

In theory, there’s a chance for a process to modify thousands of file mappings and terminate before the mapped page writer activates. Rewind when a process is terminated , our process notify routine is invoked and the process entry structure is freed - we lose all tracking information we had on that process.

To handle such case , if the process terminated has created more than a threshold number of R/W sections , it’s removal from the list is deffered to a dedicated system thread :

pProcess ProcessEntry = processes::GetProcessEntry(HandleToUlong(ProcessId));

if (!ProcessEntry)

return;

ProcessEntry->Terminated = true;

ProcessEntry->OriginalPid = ProcessEntry->Pid;

ProcessEntry->Pid = INVALID_PID;

if (ProcessEntry->SectionsCount >= NUMBER_OF_SECTIONS_TO_DEFER_REMOVAL)

{

NTSTATUS status;

HANDLE ThreadHandle;

status = PsCreateSystemThread(&ThreadHandle, THREAD_ALL_ACCESS, NULL, NULL, NULL, processes::DeferredRemover, ProcessEntry);

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

{

DbgPrint("[*] could not defer removal to system thread : ( \n");

processes::RemoveProcess(HandleToUlong(ProcessId));

}

}

The system thread waits for two minutes and removes the entry. We have to “fake” the pid to avoid ambiguity conflicts(i.e. a new process is created with the same pid that have just been terminated.)

Blocking a mapped page writer write without breaking the system

So a process may be able to modify a large number of mappings before the mapped page writer activates. This is a challenge as we can’t prevent those modifications from occuring simply by killing the process, the paging writes have already been “scheduled” ,The PTEs were marked as dirty, causing the corresponding PFNs modified bit to be set. Once we know a ransomware is executing, and is using memory mapped I/O to encrypt files, it’s only right to prevent any modification to a file that is backed by a R/W section created by the said ransomware, especially since we use a statistical approach to identify encryption. We can’t block the write (i.e. by returning access denied and FLT_PREOP_COMPLETE), if we did the PFN would have remained modified, inevitably causing the mapped page writer to trigger again.

One option could be to lie and “successfully” complete the IRP.

Data->Iosb.Status = STATUS_SUCCESS;

Data->Iosb.Information = Data->Iopb->Parameters.Write.Length;

return FLT_PREOP_COMPLETE

Whilst it will indeed prevent modification, it can lead to major cache coherncey issues eventually causing applications to fail and potentially the machine to crash.

Can’t we just modify the buffer directly? Well, if you ever wrote an encryption filter it’s probably a question you already came across. To answer that, let’s talk about the cache manager.

The NT cache manager

The windows cache manager is a software-only component which is closely integrated with the windows memory manager, to make file-system data accessible within the virtual memory system. Although constant advances in storage technologies have led to faster and cheaper secondary storage devices, accessing data off secondary storage media is

still much slower than accessing data buffered in system memory, so it becomes important to have data

brought into system memory before it is accessed (read-ahead functionality), to

retain such information in memory until it is no longer needed (caching of data),

and possibly to defer writing of modified data to disk to obtain greater efficiency

(write-behind or delayed-write functionality).

Back to our question, the answer lies in the details of how the cache manager handles a cached write. You can check the Appendix for the step-by-step description. What’s relevant to us is that when a cached write is initiated, the Cc will memory map the portion of the file if it hasn’t already mapped it. If another process then comes and memroy maps the same file it will get a mapping backed by the same physical pages of those backing the Cc mapping. Manipulating the buffer directly will not only affect the data going to be written to disk, but also the state of the file in the cache. Unlike encryption filters that are often designed to transparently protect data on disk, it’s fine from RansomGuard’s perspective as the ransomware is about to corrupt that data anyways.

// if a malicious process has a R/W section object to this file we want to prevent the modification

// we cant simply deny the write as the page will remain dirty which will cause the MPW to trigger again later

// for a *cached* write the Cc memory maps the file and copies the user data into the mapping

// if someone else then comes and memory maps the file the mapping will use the same physical pages backing the Cc mapping

// when flushing dirty pages the os builds an MDL to describe the same physical pages (again, same physical pages Cc uses for the file)

// knowing that , modifying the buffer directly will cause everyone with the mapping to see the changes

// take encryption drivers for example, this is an issue as the intent is to only protect the data on disk

// in this case , we don't mind manipulating the buffer directly, as otherwise the ransomware will just corrupt the data anyway...

if (processes::CheckForMaliciousSectionOwner(&FileContx->FileName))

{

SIZE_T BytesToWrite = (WriteParams.Length >= FileSize) ? FileSize : WriteParams.Length;

PVOID OverwrittenDiskContent = (PVOID)((ULONG_PTR)DiskContent + WriteParams.ByteOffset.QuadPart);

__try

{

__try

{

RtlCopyMemory(DataToBeWritten,OverwrittenDiskContent, BytesToWrite);

DbgPrint("[*] prevented modification to %wZ by malicious process \n", FileContx->FileName);

}

__except (EXCEPTION_EXECUTE_HANDLER)

{

DbgPrint("[*] exception in attempt to prevent modification to %wZ by malicious process\n",FileContx->FileName);

}

}

__finally

{

FltReleaseContext(FileContx);

ExFreePoolWithTag(DiskContent, TAG);

ExFreePoolWithTag(DataCopy, TAG);

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

}

}

RansomGuard against Maze

RansomGuard deals with Maze comfortably , for a deatiled description of Maze check out Sophos’s blogpost : Sophos’s post.

- 11 files encrypted , 10 of which RansomGuard restored

- Maze successfully killed

- Debug output :

00000481 257.80279541 [*] R/W section is created for \Device\HarddiskVolume3\$Recycle.Bin\S-1-5-21-1519848365-1663756913-3822597310-1001\$RAL6GT6\htb-job1 - Copy.png

00000484 258.02233887 [*] backed up htb-job1 - Copy.png

00000485 258.02896118 [*] \Device\HarddiskVolume3\$Recycle.Bin\S-1-5-21-1519848365-1663756913-3822597310-1001\$RAL6GT6\htb-job1 - Copy.png encrypted by 552

00000486 258.03894043 [*] files encrypted by \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\Maze.exe -> 1

00000516 267.57147217 [*] R/W section is created for \Device\HarddiskVolume3\RansomGuard_User_Restore\htb-job1 - Copy.png

00000521 267.90890503 [*] backed up htb-job1 - Copy.png

00000522 267.91683960 [*] \Device\HarddiskVolume3\RansomGuard_User_Restore\htb-job1 - Copy.png encrypted by 552

00000523 267.96432495 [*] files encrypted by \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\Maze.exe -> 2

00000588 295.95721436 [*] R/W section is created for \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Crypto\Keys\de7cf8a7901d2ad13e5c67c29e5d1662_ 162686e5-3e74-454e-a51b-1e4ebdadf298

00000592 296.29370117 [*] backed up de7cf8a7901d2ad13e5c67c29e5d1662_162686e5-3e74-454e-a51b-1e4ebdadf298

00000593 296.30459595 [*] \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Crypto\Keys\de7cf8a7901d2ad13e5c67c29e5d1662_162686e5-3e74-454e-a51b-1e4ebdadf298 encrypted by 552

00000594 296.31512451 [*] files encrypted by \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\Maze.exe -> 3

00000598 297.99856567 [*] backed up de7cf8a7901d2ad13e5c67c29e5d1662_162686e5-3e74-454e-a51b-1e4ebdadf298

00000599 298.00854492 [*] \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Crypto\Keys\de7cf8a7901d2ad13e5c67c29e5d1662_162686e5-3e74-454e-a51b-1e4ebdadf298 encrypted by mapped page writer

00000600 298.02206421 [*] files encrypted by \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\Maze.exe -> 4

00000649 313.89920044 [*] R/W section is created for \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Protect\S-1-5-21-1519848365-1663756913-3822597310-1001\0ae5e0a7-afbf-4146-aeb8-916bbc5715e9

00000650 313.94641113 [*] [\Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Protect\S-1-5-21-1519848365-1663756913-3822597310-1001\0ae5e0a7-afbf-4146-aeb8-916bbc5715e9] pre paging write 6421 predicted paging write 7570 diff 1150

00000651 314.25094604 [*] [\Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Protect\S-1-5-21-1519848365-1663756913-3822597310-1001\0ae5e0a7-afbf-4146-aeb8-916bbc5715e9] pre paging write 5760 predicted paging write 7762 diff 2003

00000652 314.37820435 [*] backed up 0ae5e0a7-afbf-4146-aeb8-916bbc5715e9

00000653 314.38742065 [*] \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Protect\S-1-5-21-1519848365-1663756913-3822597310-1001\0ae5e0a7-afbf-4146-aeb8-916bbc5715e9 encrypted by mapped page writer

00000654 314.40267944 [*] files encrypted by \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\Maze.exe -> 5

00000700 328.47003174 [*] backed up CameraRoll.library-ms

00000701 328.47637939 [*] \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Libraries\CameraRoll.library-ms encrypted by 552

00000702 328.48638916 [*] files encrypted by \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\Maze.exe -> 6

00000704 329.65780640 [*] R/W section is created for \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Libraries\Documents.library-ms

00000709 329.95840454 [*] backed up Documents.library-ms

00000710 329.96768188 [*] \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Libraries\Documents.library-ms encrypted by 552

00000711 329.98110962 [*] files encrypted by \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\Maze.exe -> 7

00000698 328.15954590 [*] R/W section is created for \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Libraries\CameraRoll.library-ms

00000713 330.46475220 [*] backed up CameraRoll.library-ms

00000714 330.47409058 [*] \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Libraries\CameraRoll.library-ms encrypted by mapped page writer

00000715 330.48303223 [*] files encrypted by \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\Maze.exe -> 8

00000718 330.91784668 [*] R/W section is created for \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Libraries\Music.library-ms

00000721 331.42086792 [*] backed up Music.library-ms

00000722 331.42776489 [*] \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Libraries\Music.library-ms encrypted by 552

00000723 331.43615723 [*] files encrypted by \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\Maze.exe -> 9

00000724 331.66406250 [*] backed up Documents.library-ms

00000725 331.67065430 [*] \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Libraries\Documents.library-ms encrypted by mapped page writer

00000726 331.68273926 [*] files encrypted by \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\Desktop\Maze.exe -> 10

00000732 332.89422607 [*] prevented modification to \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Users\dorge\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Libraries\Music.library-ms by malicious process

00000734 333.01222278 [*] killed ransomware process!

00000735 333.76620483 [*] waiting two minutes to remove 552 process entry

Filtering file deletions

A file or directory is deleted when a deletion request is pending and the last user reference to the file is released (that is, the last IRP_MJ_CLEANUP is sent to the file system). A deletion request can be initiated in one of the following ways :

- IRP_MJ_CREATE with the

FILE_DELETE_ON_CLOSEflag set. - IRP_MJ_SET_INFORMATION with

FileDispositionInformationpassing aFILE_DISPOSITION_INFORMATIONstructure with theDeleteFileboolean set to true. - IRP_MJ_SET_INFORMATION with

FileDispositionInformationExpassing aFILE_DISPOSITION_INFORMATION_EXstructure with theFILE_DISPOSITION_DELETEset to true.FILE_DISPOSITION_ON_CLOSEcan also be set to control the delete on close state based on theFILE_DISPOSITION_DELETEflag.

There’s an interesting twist to this, the delete disposition can also be reset by calling the same IRP_MJ_SET_INFORMATION request with the FileDispositionInformation information class with the DeleteFile member set to FALSE, or with the FileDispositionInformationEx information class with the FILE_DISPOSITION_DELETE cleared. This means that the file will not be deleted from the file system once the final handle is closed, cancelling the previous request to delete the file. This call (e.g. to set DeleteFile to FALSE) will be successful regardless of whether the file had a delete disposition set or not. In fact, one can call to set and reset the disposition many times and whoever called last to set the disposition to either true or false will win.

Since the delete disposition can also be manipulated from different handles, it must be a per stream flag , again looking at the FastFat source in FatSetDispositionInfo confirms the flag is indeed part of the FCB.

- For those not familiar with the

FCBstructure , just know operations on the same on-disk object share the same file control block, referenced byFileObject->FsContext.

SetFlag( Fcb->FcbState, FCB_STATE_DELETE_ON_CLOSE );

FileObject->DeletePending = TRUE;

FCB_STATE_DELETE_ON_CLOSE is the flag determining if the file is going to be deleted or not , again based on the fastfat source.

//

// Check if we should be deleting the file. The

// delete operation really deletes the file but

// keeps the Fcb around for close to do away with.

//

if (FlagOn(Fcb->FcbState, FCB_STATE_DELETE_ON_CLOSE) &&

!FlagOn(Vcb->VcbState, VCB_STATE_FLAG_WRITE_PROTECTED)) {

But we already mentioned there’s yet another way to reuqest a delete , IRP_MJ_CREATE with the FILE_DELETE_ON_CLOSE flag set , looking at the FastFat source in FatCommonCreate :

PCCB Ccb = (PCCB)FileObject->FsContext2;

if (DeleteOnClose) {

SetFlag( Ccb->Flags, CCB_FLAG_DELETE_ON_CLOSE );

}

We can see that the flag is translated into a CCB flag, CCB_FLAG_DELETE_ON_CLOSE. The CCB (context control block) is unique per FILE_OBJECT structure, so basically the FILE_OBJECT remembers that it was opened with the FILE_DELETE_ON_CLOSE flag. The question is, where is the CCB_FLAG_DELETE_ON_CLOSE flag converted into FCB_STATE_DELETE_ON_CLOSE ?

A quick search shows this happens during IRP_MJ_CLEANUP , as shown below :

if (FlagOn(Ccb->Flags, CCB_FLAG_DELETE_ON_CLOSE)) {

NT_ASSERT( NodeType(Fcb) != FAT_NTC_ROOT_DCB );

//

// Transfer the delete-on-close state to the FCB. We do this rather

// than leave the CCB_FLAG_DELETE_ON_CLOSE flag set so that if we

// end up breaking an oplock and come in again we won't try to break

// the oplock again (and again, and again...).

//

SetFlag( Fcb->FcbState, FCB_STATE_DELETE_ON_CLOSE );

ClearFlag( Ccb->Flags, CCB_FLAG_DELETE_ON_CLOSE );

ProcessingDeleteOnClose = TRUE;

the usage of the CCB flag for delete on close has some implications worth noting :

- Since the

FCBflag isn’t set up until cleanup, anIRP_MJ_QUERY_INFORMATIONrequest with theFileStandardInformationinformation class will return theDeletePendingflag set to FALSE even though the file is going to be deleted. - Trying to set the

DeleteFileflag to FALSE will have no effect since theFILE_DISPOSITION_INFORMATIONstructure only affects theFCB_STATE_DELETE_ON_CLOSEflag and not theCCBone, which will eventually be promoted to the FCB. - To clear the delete on close state , one can issue an

IRP_MJ_SET_INFORMATIONrequest with theFILE_DISPOSITION_INFORMATION_EXstructure enabling theFILE_DISPOSITION_ON_CLOSE

One interesting issue we are going to face when tracking file deletes is the fact the NT I/O stack is asynchronous and as such the order in which a minifilter sees requests is not necessarily the order in which the file system sees them. Consider two IRP_MJ_SET_INFORMATION requests with the FileDispoisitionInformation class. One in which the DeleteFile flag is set to true and another to false. Moreover , they are racing in a way that the filter sees both pre operation callbacks before it sees the post operation callback for either of them (in other words, both requests are being processed by layers below the filter at the same time). When a filter sees these requests it might see the one that sets it to TRUE and then the one that sets it to FALSE and assume that the delete disposition was set and then reset and so the file won’t be deleted. However, it’s very possible that the file system will receive the request that sets the delete disposition to FALSE before the one that sets it to TRUE and, so it will delete the file. This is not necessarily a frequent case but it can happen (e.g. a minifilter below us in the stack pended the request).

Rewind the reason we are interested in deletes are the following sequences of operations:

Extending the driver

Up until now we filtered out any request not asking for write access. Time to extend our driver to filter requests that may end up delete the file.

bool DeleteOnClose = FlagOn(params.Options, FILE_DELETE_ON_CLOSE);

bool DeleteAccess = params.SecurityContext->DesiredAccess & DELETE;

bool WriteAccess = params.SecurityContext->DesiredAccess & FILE_WRITE_DATA;

if (!WriteAccess && !DeleteOnClose && !DeleteAccess)

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

If FILE_DELETE_ON_CLOSE is set , take an initial datapoint.

// if file is marked for deletion

if (DeleteOnClose)

{

bool NotExists = utils::IsFileDeleted(FltObjects->Filter, FltObjects->Instance, &FileNameInfo->Name);

if (!NotExists)

{

CreateContx->PreEntropy = utils::CalculateFileEntropyByName(FltObjects->Filter, FltObjects->Instance, &FileNameInfo->Name, FLT_CREATE_CONTEXT, CreateContx);

if (CreateContx->PreEntropy == INVALID_ENTROPY)

{

FltFreePoolAlignedWithTag(FltObjects->Instance, CreateContx, TAG);

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

}

CreateContx->CalculatedEntropy = true;

}

// no need to check for truncation if the file is marked for deletion we will not evaluate the write regardless

*CompletionContext = CreateContx;

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_WITH_CALLBACK;

}

Revisit our extended context structure :

typedef struct _HandleContext

{

PFLT_FILTER Filter;

PFLT_INSTANCE Instance;

UNICODE_STRING FileName;

UNICODE_STRING FinalComponent;

ULONG RequestorPid;

bool WriteOccured;

double PreEntropy;

double PostEntropy;

PVOID OriginalContent;

ULONG InitialFileSize;

bool SavedContent;

bool CcbDelete;

bool Truncated;

bool FcbDelete;

bool NewFile;

int NumSetInfoOps;

}HandleContext, * pHandleContext;

We also have to start filtering new files, as long as they are opened with write access.

const auto& params = Data->Iopb->Parameters.Create;

bool NewFile = (Data->IoStatus.Information == FILE_CREATED);

// we are not interested in new files not opened for writing

if (NewFile && (params.SecurityContext->DesiredAccess & FILE_WRITE_DATA) == 0)

{

if (PreCreateInfo->SavedContent)

ExFreePoolWithTag(PreCreateInfo->OriginalContent, TAG);

FltFreePoolAlignedWithTag(FltObjects->Instance, CompletionContext, TAG);

return FLT_POSTOP_FINISHED_PROCESSING;

}

Lastly, mark our context accordingly :

HandleContx->CcbDelete = PreCreateInfo->DeleteOnClose;

HandleContx->NewFile = NewFile;

Managing CCB_FLAG_DELETE_ON_CLOSE and FCB_STATE_DELETE_ON_CLOSE

We are only interested in IRP_MJ_SET_INFORMATION requests with either the FileDispositionInformation or FileDispositionInformationEx information classes.

To handle racing deletes , we maintain a context counter field NumOfSetInfoOps to represent the number of changes to the delete disposition in flight. If there’s already some operations in flight, no point calling our post operation. Since there will be no post operation (where the counter is decremented) , the value will forever stay 1 or more , which is one of the conditions we will check for at cleanup to consider the file as a deletion candidate.

Our pre set information filter :

switch (Data->Iopb->Parameters.SetFileInformation.FileInformationClass) {

case FileDispositionInformation:

case FileDispositionInformationEx:

pHandleContext HandleContx = nullptr;

NTSTATUS status = FltGetStreamHandleContext(FltObjects->Instance, FltObjects->FileObject, reinterpret_cast<PFLT_CONTEXT*>(&HandleContx));

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

HandleContx->NumSetInfoOps++;

// handle racing deletes , in such case we will have to check if the file was actually deleted post cleanup

if (HandleContx->NumSetInfoOps > 1)

{

FltReleaseContext(HandleContx);

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

}

// capture initial datapoint if we don't already have one

if (!HandleContx->SavedContent)

{

HandleContx->PreEntropy = utils::CalculateFileEntropy(FltObjects->Instance, FltObjects->FileObject, HandleContx, true);

}

// pass context to post

*CompletionContext = HandleContx;

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_WITH_CALLBACK;

}

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

}

We use our potstop IRP_MJ_SET_INFORMATION handler to update the state of FcbDelete & CcbDelete :

if (NT_SUCCESS(Data->IoStatus.Status)) {

if (Data->Iopb->Parameters.SetFileInformation.FileInformationClass == FileDispositionInformationEx) {

ULONG flags = ((PFILE_DISPOSITION_INFORMATION_EX)Data->Iopb->Parameters.SetFileInformation.InfoBuffer)->Flags;

if (FlagOn(flags, FILE_DISPOSITION_ON_CLOSE)) {

HandleContx->CcbDelete = BooleanFlagOn(flags, FILE_DISPOSITION_DELETE);

}

else {

HandleContx->FcbDelete = BooleanFlagOn(flags, FILE_DISPOSITION_DELETE);

}

}

else {

HandleContx->FcbDelete = ((PFILE_DISPOSITION_INFORMATION)Data->Iopb->Parameters.SetFileInformation.InfoBuffer)->DeleteFile;

}

}

// operation is over , decrement active set info ops

HandleContx->NumSetInfoOps--;

FltReleaseContext(HandleContx);

return FLT_POSTOP_FINISHED_PROCESSING;

In our evaluation worker , we will check if the file was actually deleted in case it was a deletion candidate. If so , a new entry for it will be constructed in the corresponding process entry structure , allowing us to maintain state across different file objects.

typedef struct _DeletedFile

{

UNICODE_STRING Filename;

PVOID Content;

ULONG Size;

double PreEntropy;

LIST_ENTRY* Next;

}DeletedFile, * pDeletedFile;

To check if a file is deleted we can either call FltQueryInformationFile and check for STATUS_FILE_DELETED or try and open the file and check for STATUS_OBJECT_NAME_NOT_FOUND , which is what we check for in utils::IsFileDeleted :

// if delete on close was set , delete pending was set or there was a racing set disposition check if the file was deleted

if (HandleContx->CcbDelete || HandleContx->FcbDelete || HandleContx->NumSetInfoOps > 0)

{

if (utils::IsFileDeleted(HandleContx->Filter, HandleContx->Instance, &HandleContx->FileName))

{

files::AddDeletedFile(&HandleContx->FileName, HandleContx->OriginalContent,HandleContx->InitialFileSize, HandleContx->RequestorPid,HandleContx->PreEntropy);

FltReleaseContext(HandleContx);

FltFreeDeferredIoWorkItem(FltWorkItem);

FltCompletePendedPostOperation(Data);

return;

}

}

Finally , whenever a write is initiated to a monitored new file , we will check if it was previously deleted by the process. If so , the datapoint stored under the process entry structure is copied to the file object context. We have to make a technical definition as to what we refer to when using the term “same file”. Consider a Word document. User opens X.DOCX, deletes some of it, adds some more, and saves it. Is that the same file that he opened? Suppose he saves it with a different name? Is it the same file now? The potential permutations are endless. Since ransomwares have a tendency for changing file extensions will define “same file” as a file with the same full name , ignoring the extension.

// we are only interested in new files that have been previously deleted by the same process (same name ignoring the extension)

// if that's the case , copy original content and size into the context's initial datapoint and mark it for evaluation (HandleContx->WriteOccured)

// then free resources owned by the process entry , so the resources's lifetime is more accurate (file object lifetime over process lifetime)

// otherwise no need to mark HandleContx->WriteOccured as there's no point evaluating

if (HandleContx->NewFile)

{

DeletedData DeletedFileData = files::GetDeletedFileContent(&HandleContx->FileName, HandleContx->RequestorPid);

if (DeletedFileData.Content)

{

// if it's the first write to this new file

if (!HandleContx->WriteOccured)

{

// copy datapoint from process entry to context

HandleContx->InitialFileSize = DeletedFileData.Size;

HandleContx->OriginalContent = ExAllocatePoolWithTag(NonPagedPool, DeletedFileData.Size, TAG);

if(!HandleContx->OriginalContent)

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

RtlCopyMemory(HandleContx->OriginalContent, DeletedFileData.Content, DeletedFileData.Size);

HandleContx->PreEntropy = DeletedFileData.PreEntropy;

HandleContx->WriteOccured = true;

HandleContx->SavedContent = true;

// remove deleted file from process entry

files::RemoveDeletedFileByName(&HandleContx->FileName, HandleContx->RequestorPid);

}

}

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_NO_CALLBACK;

}

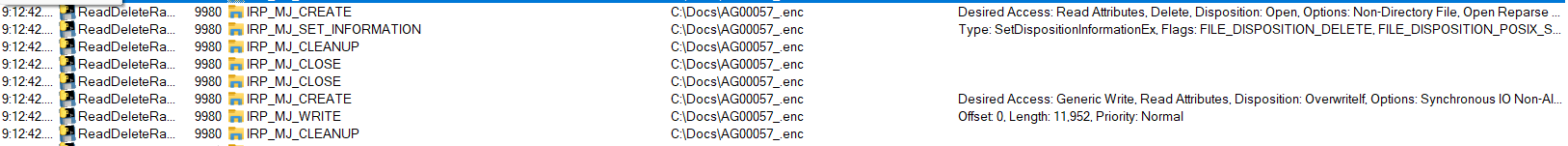

From there on , RansomGuard will evaluate the file object normally , capturing the second datapoint at post cleanup. To test RansomGuard, We will use a sample that initiates the following operations for every file on the C drive :

Since we set a threshold for number of deleted files we are going to keep track of per process , a decision was made to lower the number of encryptions to be consdiered as ransomware (from 10 to 6). Again , RansomGuard has the upper hand :

- 6 files encrypted , 6 of which RansomGuard restored

- Ransomware process successfully killed

- Debug output :

[*] Encryption Detected [*] files encrypted by ReadDeleteRansom.exe -> 1 [*] backed up \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Docs\DEBUGME1.enc [*] files encrypted by ReadDeleteRansom.exe -> 2 [*] Encryption Detected [*] backed up \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Docs\DEBUGME2.enc [*] files encrypted by ReadDeleteRansom.exe -> 3 [*] Encryption Detected [*] backed up \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Docs\DEBUGME3.enc [*] files encrypted by ReadDeleteRansom.exe -> 4 [*] Encryption Detected [*] backed up \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Docs\DEBUGME7.enc [*] files encrypted by ReadDeleteRansom.exe -> 5 [*] Encryption Detected [*] backed up \Device\HarddiskVolume3\Docs\DEBUGME78 (1).enc [*] files encrypted by ReadDeleteRansom.exe -> 6 [*] killed ransomware process!

Wrapping up

RansomGuard is not perfect and there are ways around it’s heuristics for sure, from using IPC to break per-process context, directly sending IRPs to NTFS or lowering the encrypted entropy by partial encryption. Having said that, RansomGuard does detect and prevent the vast majority of successful ransomwares operating in the wild, which is cool. I’d like to use this opportunity to thank Matti & Jonas for their respective contributions throughout the R&D process. As always, feel free to contact me on X for any questions, feedback, or otherwise, you may have! Thanks for reading!

Appendix - cached write operation

The details behind a cached write can be described in an 11-step process.

- A user application initiates a write operation, which causes the control to be

transferred to the I/O Manager in the kernel.

- The I/O Manager directs the write request to the appropriate file system

driver using an IRP. the buffer may be mapped to system space , or an mdl may be created or the virtual address of the buffer may be directly passed.

- The file-system driver recivies the IRP , as long as the operation is buffered (

FILE_FLAG_NO_BUFFERING) was not passed to CreateFile) , if caching has not yet been initiated for this file, the file system driver initiates caching of the file by invoking the Cache Manager(Cc). The Virtual Memory Manager (Mm) creates a file mapping (section object) for the file to be cached. - The file system driver simply passes on the write request to the cache manager via

CcCopyWrite - The cache manager examines its data structures to determine whether there is a mapped view for the file containing the range of bytes being modified by the user. If no such mapped view exists, the cache manager creates a

mapped view for the file region.

- The cache manager performs a memory copy operation from the user’s buffer to the virtual address range associated with the mapped view for the file.

- If the virtual address range is not backed by physical pages, a page fault occurs and control is transferred to the

Mm

. - The

Mmallocates physical pages, which will be used to contain the requested data - The cache manager completes the copy operation from the user’s buffer to the virtual address range associated with the mapped view for the file

- The cache manager returns control to the file system driver. The user data is now resident in system memory and has not yet been written to storage. So when is the data actually transfered to storage ? the Cc’s lazy writer is responsible to decrease the window in which the cache is dirty by writing cached data back to storage , it coordinates with the mapped page writer thread of the

Mmwhich is responsible to write dirty mapped pages back to storage whenever a certian threshold is met (there’s also the modified page writer which shares similar responsbility , with pagefiles).

The noncached write to storage may be initiated by either of them - The file system driver completes the original IRP sent to it by the I/O manager and the I/O manager completes the original user write request

Appendix - partial encryption

Recently, a new trend has emerged in the ransomware scene, instead of fully encrypting files, only partially encrypting them. Usually, either only the first X number of bytes are encrypted or the file is divided to N number of segments of a fixed size based on the file size, encrypting only some of the segments, leaving others unchanged. In such case, there’s much more similarity between the original and encrypted versions of the file, posing a drastic challenge to solutions that leverage statistical methods, being the majority of mdoern anti-ransomware solutions, including RansomGuard. Partial encryption comes with it’s own downsides, as demonstrated by CyberArk’s team White Phoenix tool, able to recover important data from partially encrypted files. In the context of RansomGuard, a raw idea is to in addition to analyzing the entropy of the entire file content, divide the file into N segments based on the file size (just like a ransomware would do) and calculate each’s segment entropy inidividually. If a threshold precentage of segments seem to have suspicously high entropy it may indicate encryption. The closer the number of segments we divide the file into will be to the number of segments the ransomware divide the file into, the higher the chances we will be able to identify a malicious pattern. Again, it’s only a raw idea I haven’t actually tested, maybe sometime in the future.